|

|

Research HighlightVA Suicide Prevention: From Risk Factors to At-Risk VeteransKey Points Suicide prevention is VA’s top clinical priority.

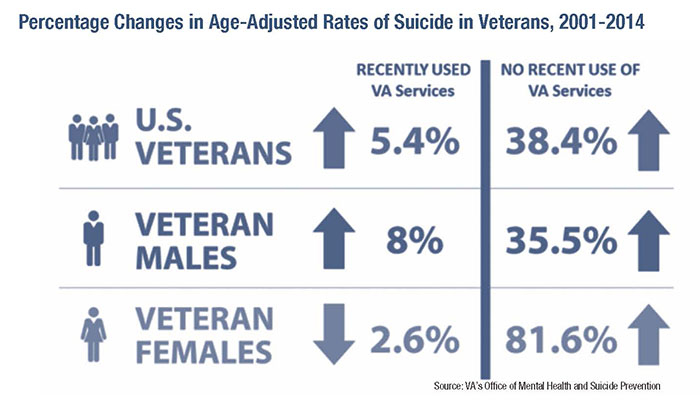

Veteran suicide is a national concern. VA has documented that suicide rates among patients receiving care in the VA health system exceed those found in the US adult population. Preventing suicide is VA’s top clinical priority. Additional approaches are needed, however, to address suicide as a public health priority. VA has expanded mental health access and implemented innovative suicide prevention services.1 Consistent with Beverly Pringle’s call to better know “whom to target, with which interventions, and in what order of priority,” as part of innovative prevention efforts, VA has developed suicide predictive modeling.2 In 2016, this work moved beyond proof of concept with implementation of the Recovery Engagement And Coordination for Health – Veterans Enhanced Treatment (REACH VET) program. Through REACH VET, facilities receive information regarding patients in their top 0.1 percent tier of predicted risk based on indicators in the electronic health record. REACH VET shifts the focus of suicide analytics from individual risk factors to individuals at risk, and supplements clinical approaches to risk assessment. There was consideration of the feasibility of systematically quantifying individuals’ suicide risk as early as the mid-1950s. It was regarded then as impractical, given concerns about the anticipated large number of false positives and it was argued that trying to address this by focusing on individuals determined to be at highest risk would drastically reduce the number of correctly identified suicidal patients. By the early 1970s, perhaps with changing expectations that prevention services could include outpatient care, suicide risk calculation was considered potentially practicable. Over 40 years later, VA has demonstrated that health systems can systematically assess suicide risk concentration and employ this information to support suicide prevention. There are three main approaches to characterize suicide risk concentration. First, as part of routine clinical care, individual providers consider their patients’ well-being via clinical assessments and in light of known risk factors. The literature identifies many factors associated with suicide. These include demographic measures (e.g., male gender), clinical diagnoses (e.g., bipolar disorder, depression), and contextual and temporal factors (e.g., rural residence, time since inpatient psychiatric discharge, and suicide attempts). However, effect sizes of individual associations are typically small considering suicide’s low event rate. Also, many suicides occur among individuals without salient suicide risk factors. Such individual assessments would be unwieldy as population-level prevention strategies. A second approach, use of data mining and decision tree algorithms to identify high-risk profiles, has been explored, however this has yielded such individualized profiles that they would be difficult to implement broadly. A third strategy is to evaluate predictive modeling to estimate levels of risk for individual patients. VA’s proof of concept work regarding suicide risk concentration followed this approach, using clinical and administrative data that are routinely collected as part of VA electronic health record systems.2 With the involvement of the National Institute of Mental Health, VA developed a predictive model that included over 100 concepts and 381 predictors for patient-months over a three year period for all suicide decedents and 1 percent of living patients, divided randomly into development and validation samples. Predictors included measures thought to be risk factors, specific events entered as lag variables, and interactions known to be important. For example, predictors included age, gender, marital status, mental health diagnoses, utilization, psychotropic medication receipt, and any documented suicide attempts. Parameters from the logistic regression used for the development sample were used to estimate risk of suicide in the validation sample. To explore the persistence of risk, beyond the index month, they were also applied to a cohort of all VHA patients alive as of 9/30/2010 and risk concentration was assessed over the next 12 months. Risk concentration was measured as the number of observed suicide deaths divided by the expected number if suicide risk were randomly distributed. Modeling demonstrated that suicide rates in the development and validation samples were 39 and 30 times greater in the highest 0.10 percent tier of predicted risk, respectively, as compared to expected rates if suicide risk were randomly distributed. Of the patients in the top 0.1 percent tier of predicted risk, only 21 percent had received a high-risk flag for suicide based on clinical grounds. Suicide risk concentration remained substantially elevated over the subsequent 12 months. The model also predicted death from other external causes and, to a lesser degree, overall non-suicide mortality, mental health hospitalizations, medical-surgical hospitalizations, and suicide attempts.

To address problems of correlated measures and to develop a more parsimonious model for operational implementation, VA collaborated with scientists at Harvard University to apply machine learning methods that determine the optimal number of predictors and that select predictors for a new model.3 This was accomplished with similar predictive power using a model with 61 predictors. The Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention has developed innovative tools to notify providers of risk assessment results for their patients and to ask providers to reevaluate and enhance care as appropriate in collaboration with the Veteran. This work was completed by the Program Evaluation Resource Center (PERC) at a remarkable pace and with an ongoing process of modifications to address concerns from the field. REACH VET national program evaluation is ongoing at the Serious Mental Illness Treatment Resource and Evaluation Center (SMITREC). This work is supplemented by ongoing formative evaluation work funded by QUERI and led by Sara Landes. In considering the swift development and implementation of REACH VET, it is appropriate to recognize some core strengths of the nation’s largest integrated health system. REACH VET implementation benefited from VA’s close engagement with federal and non- federal scientific partners, active leadership support, a national electronic health record system, innovative field support and program dissemination capabilities, established systems for surveillance and analytics, and the extraordinary efforts of VA professionals dedicated to the mission of serving Veterans. It is also important to look to the future. The current program identifies and enhances care for VA patients at the highest risk. Future work should extend these enhancements to address the larger group with more moderate risk to make a larger difference in the system as a whole. References

|

|