|

|

Research HighlightVery Low Food Security: A Major Threat to Veteran Well-beingKey Points

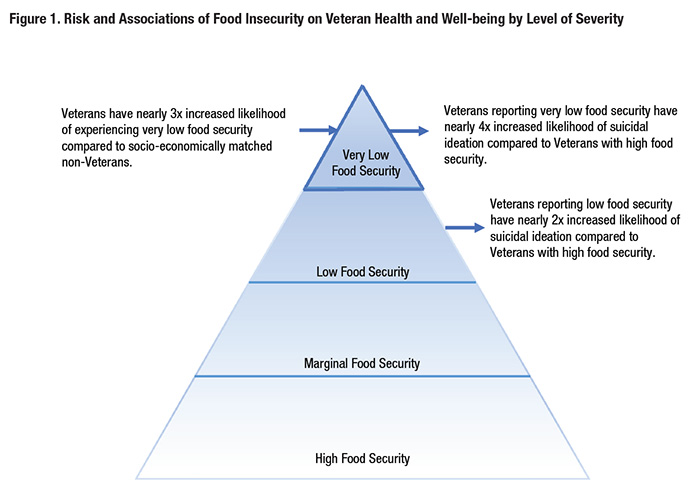

Veterans need adequate access to nutritious food for their health and wellness. However, food insecurity can threaten their ability to achieve this need. Food insecurity is a socio-economic condition in which individuals lack money to purchase adequate, nutritious food. In a study we recently published of post-9/11 Veterans living in low-income households, Veterans described skipping meals or reducing their intake to conserve food for their children and other family members.1 They also described having to purchase affordable and filling foods that often fell below their nutritional standards or were not items they preferred to eat. These compromises to their diet are consistent with characteristics of individuals living with very low food security–the most severe level of food insecurity. Food insecurity as described by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has different levels of severity (Figure 1.) Most Veterans live with high food security, meaning they have no reported food-access problems or limitations. Marginal food security is the next level of severity and is associated with anxiety over food sufficiency or shortage. Individuals with high and marginal food security are labeled food secure. Low food security is associated with reduced quality, variety, or desirability of diet. Very low food security is also associated with these characteristics along with disrupted eating patterns and reduced food intake. Individuals with low and very low food security are labeled food insecure. Research often categorizes Veterans as either food secure or food insecure based on these labels. However, our research has found important differences between the four levels of severity as they relate to Veterans. Using data from the 2011-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, we compared odds for food insecurity between working-age Veterans (n=155) and non-Veterans (n=310) matched on gender, race/ethnicity, education, and income.2 We adjusted our logistic regression model for these characteristics along with age, education, marital status, and depression screening score. We could not control for Veteran enrollment in VHA care. We found that Veterans were almost three times more likely to experience very low food security compared to socio-economically matched non-Veterans. This finding suggests that Veterans who are food insecure are suffering from the most extreme level of food insecurity. A possible explanation for the greater odds of very low food security among Veterans may be related to their military training and experience. In our prior photo-elicitation study, Veterans living in low-income households described rationing their intake as a routine part of their daily life.1 Many also continued to live by the motto of “making do with what we got” and expressed strong reluctance to seek assistance from food pantries or similar charitable donations. This military ethos needs to be considered when designing and implementing programs to assist Veterans with basic social needs such as food. Skipping meals and reducing food intake also have negative effects on health and wellness. In a separate analysis using data from the 2007-2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, we investigated the odds for depression and suicidal ideation among Veterans who reported marginal, low, and very low food security.3 Adjusting for gender, age, income-to-poverty ratio, race/ethnicity, and education level, we found that Veterans (n=2,630) with marginal, low, and very low food security had significantly increased depression symptoms as reported on the PHQ-9 compared to Veterans who were food secure. Veterans with low food security were also twice as likely to report suicidal ideation, and Veterans with very low food security were almost four times more likely to report suicidal ideation compared to Veterans with high food security. This suggests that suicide screening and intervention programs must consider Veterans’ access to basic needs, as lack of access to adequate food can be a contributing factor to Veteran stress and mental health difficulties. As research on the associations between food insecurity and Veteran well-being continues to expand, we encourage analysis by levels of food security severity as shared in Figure 1. Otherwise, significant differences may go undetected.

Of equal importance is the need to identify Veterans who are struggling with food insecurity. VHA medical centers and clinics have taken a critical step forward by building food security screening into the electronic health record. Clinicians and other members of patient-aligned care teams can mitigate food insecurity by providing Veterans who screen positive with available resources, while keeping in mind that their needs may go beyond food assistance programs. Cumulatively, our findings indicate that food insecurity is a complex issue and serious threat to the well-being of Veterans. Research, practice, and policy need to merge to ensure that no Veteran goes hungry. References

|

|