|

|

Research HighlightDifferences in Burnout between VA Women's Health PCPs and General PCPsKey Points

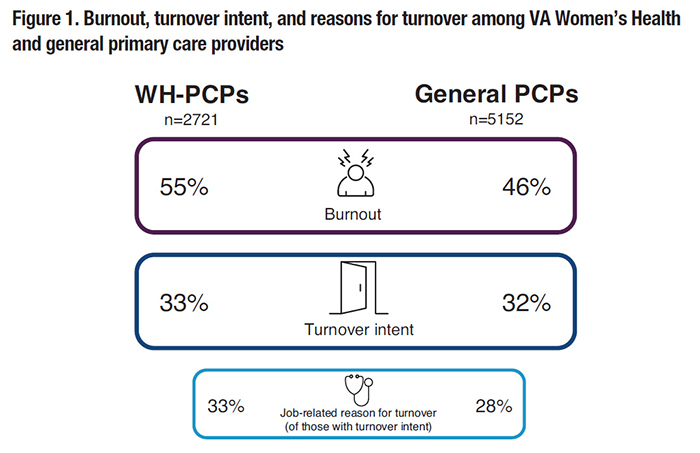

Burnout is high in VA primary care, affecting 45 to 55 percent of providers. High burnout can be associated with increased turnover, reduced patient safety, poorer quality of care, and worse doctor-patient relationships. Drivers of burnout in VA primary care are multifactorial, including difficulties with patient-aligned care team (PACT) model components (e.g., working with the call center),1 poor job-person fit,2 challenges with task delegation, and low levels of staffing. Women are a numerical minority among the VA patient population, largely due to the historically low participation of women in the military. However, they are the fastest growing segment of new users, and need to be assured of access to high quality, comprehensive primary care. To address their needs, VA has mandated availability of Women’s Health Primary Care Providers (WH-PCPs) at every facility to consolidate their care among trained and proficient providers. Over 80 percent of women Veterans receive care from WH-PCPs, and 75 percent of WH-PCPs have participated in a VA mini-residency on women’s health issues. While care provided by WH-PCPs is of higher quality and receives higher patient ratings than care provided by general PCPs, WH-PCPs face many challengesin caring for women Veterans, as they have more service-connected disabilities, use more healthcare services, and have more exposure to harassment, trauma, and violence compared to men. These unique needs, as well as the lack of specialized non-provider staff, may contribute to higher burnout among WH-PCPs. To study this issue, we examined differences in burnout and intent to leave practice between WH-PCPs and general PCPs, adjusting for provider- and facility-level characteristics. Approach to Studying Differences between WH-PCPs and General PCPsOur team created a sample of PCPs (physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants; including, 2,751 WH-PCPs and 5,152 general PCPs) from the 2017 to 2019 waves of theVA All Employee Survey, which recorded greater than 60 percent response rates in all three years. Respondents were considered burned out if they stated that they experienced emotional exhaustion or depersonalization once a week or more. Data on intended turnover within the next year, and the reasons for that turnover were also collected. We also obtained provider-level data on WH-PCP status, gender, race, ethnicity, length of job tenure, and supervisory role status. We linked individual response data to the facilities where providers worked. Facility data from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse and the VA Office of Women’s Health included medical center vs. community-based outpatient clinic status, presence of a comprehensive women’s health clinic, patient visit volume, support staff per PCP, observed-to-expected panel size, average Nosos (Greek for “chronic disease”) risk adjustment score, academic affiliation, geographic region, and rurality. We pooled the cross-sectional data across model outcomes, with survey year, provider and facility characteristics, and the interaction between provider gender and WH-PCP designation as model covariates. WH-PCPs Reported Higher Burnout but Similar Intentions to Leave VABetween 2017 and 2019, WH-PCPs were more likely to be burned out compared to general PCPs (55 percent vs. 46 percent; Figure 1), and were more likely to report burnout, even after adjusting for other provider- and facility-level factors. Despite these burnout differences, turnover rates were similar (33 percent vs. 32 percent) and were not related to provider type (i.e., WH- or general PCP). However, WH-PCPs (33 percent) who intended to leave VA were more likely to describe their reason for leaving as job-related (e.g., type of work), compared to general PCPs (28 percent).

The drivers of this burnout disparity are still unclear, but WH-PCPs may be experiencing stressors that are not easily captured in the available data. Interestingly, WH-PCPs have similar or lower workloads compared to general PCPs by conventional measures (patient encounters, staff-to-provider ratios, panel sizes), and WH-PCPs are permitted lower panel sizes if a majority of their patients are women Veterans, given their physical and mental health comorbidities on average. That said, our Nosos risk adjustment measure of facility-level patient clinical complexity captures few patient social conditions (e.g., homelessness related to mental health) and does not include exposures to sexual trauma or intimate partner violence in the military, both of which are prevalent among women Veterans who rely on VA for care. Therefore, the complexity of women’s clinical risks may not be accurately represented by standard risk adjustment, so women Veterans’ clinical complexity could still be contributing to these differences in burnout through longer, more complex patient visits. Colleagues at our Center recently conducted qualitative interviews among WH-PCPs who no longer deliver women’s primary care, and data from these interviews may inform practice and policy changes capable of addressing this burnout disparity. The burnout literature suggests that organizational approaches are most effective at combating this phenomenon, and that understanding the organizational drivers of burnout is key to improving provider well-being. The new VHA- wide Reduce Employee Burnout and Optimize Organizational Thriving (REBOOT) Task Force will benefit from this and related work as recommendations emerge for how we can support providers, teams, and facilities in their quest to reduce burnout. References

|

|