|

|

Research HighlightPeer-Supported Whole Health Coaching: A Novel Intervention to Improve the Health of High-Need Homeless VeteransKey Points

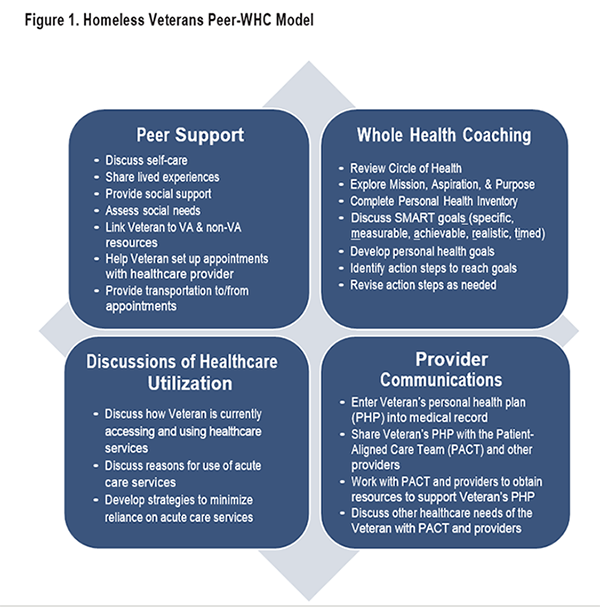

A small percentage of patients typically account for the majority of the total acute care costs in a healthcare system (emergency department visits, inpatient stays). Among these so-called “super utilizers,” housing instability is common, particularly among Veterans. Intensive outpatient programs have been implemented to support the complex needs of homeless adults and are often combined with analytics to target those at highest risk of rehospitalization. Homeless Patient Aligned Care Teams and the Homeless Registry’s “Hot Spotter” dashboard are examples of these approaches in VHA. However, intensive outpatient programs have not proven scalable or homeless adults, signaling a need for other approaches to provide high-quality care. Peer Support and Patient-Centered Care: Essential ComponentsPeer support and patient-centered care are essential components of high-quality care for high-need homeless Veterans. Peer specialists (“peers”) are Veterans with lived experience of addiction, mental illness, and/ or homelessness who are trained to support those actively struggling with these issues. Peers increase patients’ engagement in their care and can provide the time and attention that is necessary to support the needs ofhomeless Veterans. However, data supporting the effectiveness of peers to reduce acute care costs for homeless Veterans is lacking, and existing peer models do not focus on patient goals and preferences. Whole Health Coaching (WHC) is a patient-centered approach to care that focuses on “what matters to you” instead of “what is the matter with you.” Whole Health Coaches identify patients’ values and goals, which are used to guide development of health plans oriented to one’s personal health goals and care priorities. Though WHC has been shown to improve patient engagement in Veterans, it has not been tested with homeless Veterans nor subjected to a randomized controlled trial or integrated with the core functions of peers. Peer-Supported Whole Health Coaching (“Peer-WHC”) was developed to fill this gap in care for homeless super-utilizers. This approach uses data analytics (VA’s Hot Spotter dashboard) to identify homeless super-utilizer Veterans and pair them with a peer trained in WHC. In coordination with patients’ primary care teams, peers support patients’ personal health goals via linkage and engagement in supportive care services with the goal of reducing costs and improving Veterans’ health. Peer Specialists and WHC have already been implemented VA-wide and will be expanding in primary care, per recent legislation.1 Thus, Peer-WHC may offer a more scalable approach to supporting the needs of homeless super-utilizer Veterans. Formative Research of Peer-WHCDevelopment of Peer-WHC and pilot testing to evaluate its feasibility and acceptability was supported through intramural funds from VA’s National Center on Homelessness Among Veterans.2 Twenty Veterans from three outpatient primary care clinics at a VHA medical center were identified from the Homeless Registry’s Hot Spotter dashboard and enrolled in a single-arm pilot trial. These Veterans were offered 12 weekly sessions with a peer, which included discussions of their healthcare utilization patterns and peers’ outreach to the Veteran’s primary care team to assist with care coordination. The major components and activities of the Peer-WHC model are provided in Figure 1. Among the 20 Veterans who enrolled and completed a baseline interview, 17 completed a follow-up interview three months later to measure engagement and satisfaction with the intervention and changes in patient activation, perceptions of health, and hospitalizations. The follow-up interview also included a qualitative component to identify facilitators and barriers to patients’engagement with the intervention. Two peers who worked on the study and six VA staff who were providers of the participants and/or leaders of the outpatient clinics were also interviewed at the end of the study to evaluate the implementation of the intervention in the primary care context. Despite enrollment occurring almost entirely during the first year of the COVID- 19 pandemic, the intervention exceeded expectations for both engagement (median of seven peer sessions completed, almost all by phone) and satisfaction (Mean of Client Satisfaction Questionnaire total scores = 28.75 out of 32). Per self-report and qualitative data, patients’ perceptions of their health improved significantly, particularly their social health and general well-being. In the three months before and after enrollment, 45 percent and 15 percent of the sample, respectively, were hospitalized. Overall, findings suggested Veterans were engaged and satisfied with Peer-WHC and perceived it as beneficial to their health. However, the qualitative analyses and fidelity data also identified three key modifications to the intervention that may increase patient engagement and facilitate its implementation.

Using Data Analytics and Targeted Whole Health Coaching to Reduce Frequent Utilization of Acute Care among Homeless Veterans (IIR 19-187)A Hybrid I RCT is now underway to test the effectiveness and implementation potential of Peer-WHC.3 This HSR-funded study began in January 2022 and will enroll 220 homeless super-utilizer Veterans across three VHA medical centers. Key design elements include the following:

This hybrid trial is the first RCT to test the effectiveness of an intensive outpatient program for homeless super-utilizer Veterans. The significance of this work is underscored by the predominance of housing instability among super-utilizer Veterans. By testing the effectiveness and implementation potential of this integration of data analytics, peer support, and WHC, VHA and other integrated healthcare systems can evaluate the value of this model for reducing frequent use of acute care in homeless adults while maintaining quality of care.

References

|

|