|

|

Research HighlightVA Physician Burnout and Its Implications: What We Know and Why We CareKey Points

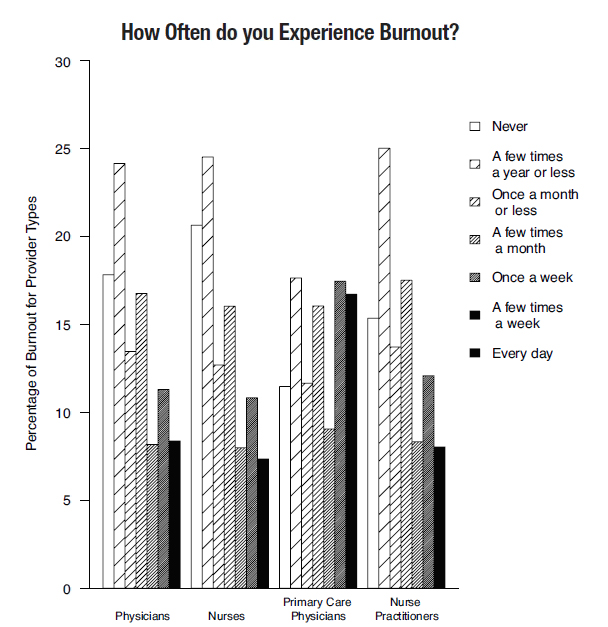

Experts agree that physician burnout is more than just being exhausted or stressed out. Burnout includes people’s whole relationship with their work and their experience of the usual stresses involved in carrying out their tasks. For this reason, the same factors that define core job requirements also define job-specific stress zones. When meeting those core job requirements becomes challenging, they become stressors and—with repeated stress—can create burnout. In other words, burnout has a social focus. It reflects more than people’s personality or coping skills; it is a person-job interface that is closely connected to organizational settings, workplace culture, work systems, and job processes. While Burnout has a Social Focus, It has Business ImplicationsPrevious research on provider burnout has stated its impact on both the mission and bottom line of healthcare organizations. For example, Swenson and Shanafelt (2017) reported a direct relationship of physician burnout to clinical and organizational performance metrics. They explained that burnout impedes access to care in two ways: it causes negative impact on the care provided, and it makes providers less willing to stay with their organization. Research also connected burnout with actual reductions in full-time employment positions over the following 24 months (Shanafelt et al., 2016), and reported correlations between burnout and ratings of quality and safety culture, as well as quality and safety standards (Lee et al., 2013). Across the VA healthcare system, ensuring access to care is a strategic priority, as reflected by the MISSION Act. Safety and quality culture also is among the key lines of effort. Given these priorities, it is important to proactively assess and address provider burnout, and to prevent it from causing provider shortages and ultimately hurting Veterans’ access to care. Burnout in the VA workforce is a serious concern, and at the forefront of VA’s effort to address this is VA’s focus on reducing physician burnout. Why physicians? They are a mission-critical occupation, the most expensive to replace, with the highest burnout rates among clinical providers, and they often lead other staff involved in patient care. These factors create unique demands and stressors for these providers, as well as unique opportunities for them to impact clinical care and patient outcomes in VA. VA Provider Burnout is WidespreadAs the graph below depicts, the highest burnout rates among all VA clinical providers are among primary care physicians—a mission-critical occupation. Among nurses, the highest burnout rates are among nurse practitioners.

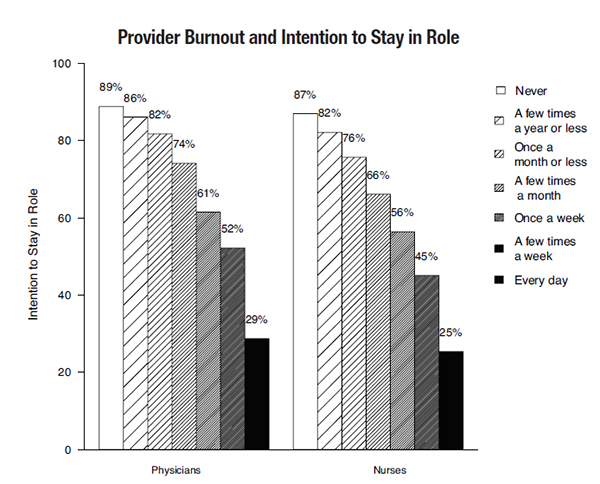

VA Providers' Experience of Burnout Shows Human Side of ProblemThe comments below, from the Patient Aligned Care Teams (PACT) 2016 survey (shared at the VA Physician Burnout summit in 2016), offer a glimpse of how it feels to be a VA physician who is experiencing burnout. VA physician on sleep deprivation and family neglect: “I am very burned out… I work 16 hours many days and get little sleep during the week and am neglecting my young daughter due to work.” VA physician speaks to overwhelming demands and new requirements: “I feel like I’m spinning here—being exhausted at the end of the day. All physicians stay way after hours to complete alerts, answer multiple calls which come all day from Call Center, answer secure messages etc., etc. It is crazy to work like this—and still come new demands and new requirements. I see too many initiatives and regulations which keep coming…” VA physician warns about effects of “bad” data: “Our team is demoralized by a consistent barrage of “Bad” data and demands to fix problems that are only problems on paper, not in practice. It’s this blind allegiance to the “Numbers” that will ultimately result in my resignation from the VA.” As the graph above depicts, VA providers burned out from their work have higher turnover intentions. They also perceive lower satisfaction from Veterans receiving care at their workplaces. This latter perception consistently and highly correlates with Veterans’ own ratings of quality of care in VA. Four Drivers of Provider BurnoutResearch outside of VA points to four drivers of physician burnout:

In VA, preliminary work shows much similarity. This research suggests the importance of systems-based interventions to reduce provider burnout. In 2016, VA hosted a virtual summit to discuss the scope, drivers, and outcomes of VA physician burnout and to outline strategic directions for improvements. Guest speakers included the Acting Under Secretary for Health and Acting Principal Deputy Under Secretary for Health. An expert group of researchers from VA and beyond, senior leaders of VA clinical programs, and VA decision-makers collaborated through working groups. They identified areas of highest leverage for VA (i.e., evaluating physicians’ workflow to allow greater delegation of administrative tasks) and generated several proposals. All summit materials are available online through the VA Workforce Surveys Portal. Start at http://aes.vssc.med.va.gov/research, go to the bottom Data Library, and select the Topic: Burnout Summit.

Reducing Burnout Requires Organizational InterventionsBurnout is a system issue and, thus, responds to organizational interventions. Most institutions incorrectly believe that managing burnout is the responsibility of individual providers. The field is dominated by tertiary interventions: addressing burnout after it occurs. More effective and less costly is pre-empting burnout from happening in the first place. Reducing burnout is more successful and better sustained when the main focus is on organizational causes (e.g., culture, work structure). Yet, organizationally focused interventions are among the least-tried and least-researched—not surprisingly, as they are the most difficult to implement. Fighting provider burnout requires coordinated efforts within organizations and strong support from organizational leaders. Transitioning to this strategy could become an aspirational target for VA. Addressing organizational factors that underlie provider burnout will help attract clinical providers, many of whom are mission-critical occupations. This designation recognizes the key importance of these employees to Veteran care outcomes. References

|

|