|

|

Research HighlightDisparities in COVID-19 Infections among Veterans Mirror General Public, but Survival Rates among Racially Diverse Veterans are ComparableKey Points

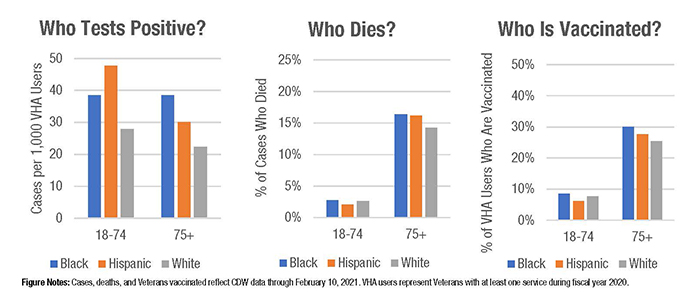

COVID-19 has devastated populations and economies in the United States and around the world. In many places, people of color have borne a disproportionate burden of disease and death associated with COVID-19. Even though a national vaccination campaign is underway and new cases are in steep decline, concerns remain that people of color will continue to be hard hit by the pandemic due to uneven vaccine availability and uptake due to structural racism and vaccine hesitancy. Given national disparities in COVID-19 related outcomes, VHA’s Office of Health Equity mobilized workgroups to allow for rapid analysis to determine how marginalized Veterans were impacted. BLUF. Black and Hispanic Veterans have received care at VA for COVID-19 infection at higher rates than White Veterans. Contrary to patterns observed in the civilian population, among Veterans who test positive, Black, Hispanic, and White Veterans have comparable survival rates. Early data indicate that Black and Hispanic Veterans have accepted COVID-19 vaccination at similar rates as White Veterans. Who Tests Positive? People of color are more likely to live in high-density residences and serve as essential workers, which increases exposure to COVID-19.1 Veterans live and work in the same communities as their families and colleagues, so it should be no surprise that Veterans of color tested positive for COVID-19 at a higher rate than White Veterans. Among those aged 18-74, Hispanic Veterans were 1.7 times more likely than White Veterans to test positive. Among those age 75 and over, Black Veterans were 1.7 times more likely to test positive. Disparities fell as the pandemic grew. Who Dies? Treatment for severely ill COVID-19 patients improved over the course of the pandemic. As experience with antivirals, antibodies, steroids, and anticoagulation increased, mortality declined. Age and comorbidities remain the major determinants of survival. Veterans aged 75 and over were 6 times more likely to die than younger Veterans. Although Veterans of color were more likely to require hospitalization when they presented with COVID-19 for care at VA, differences in mortality among Black, Hispanic, and White Veterans receiving care at VA were small. Who is Vaccinated? The CDC suggests that people aged 75 and over should be prioritized to be vaccinated for COVID-19. As of June 3, 2021, 42 percent of VHA users aged 75 and over and 36 percent of younger Veterans have been vaccinated. Despite concerns that mistrust of the healthcare system might lead to lower vaccination uptake among Veterans of color, Black and Hispanic Veterans have thus far accepted vaccination at rates similar to White Veterans. Close monitoring will be needed to ensure that disparities in vaccination availability and uptake do not emerge as VA’s vaccination campaign continues to unfold.

VA Interventions. VA success at mitigating the racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19 mortality and vaccination that have been observed outside VA may relate to several VA features and interventions. First, VA has fairly complete clinical and demographic information on VHA users; race or ethnicity data are available for about 90 percent of Veterans seen in VA during fiscal year 2020. This allowed rapid identification of disparities and outreach to at-risk groups about infection risks and potential for severe COVID-19 illness. Second, VHA users face few financial barriers to care; COVID-19 testing, care, and vaccination are available to the majority of VHA users at no cost. Perhaps most importantly, VHA users typically have established relationships with VHA providers. This allowed Veterans to be screened for COVID-19 symptoms and social risk factors, and to be counselled about masking and social distancing when they called or interacted with providers on VA Video Connect. For Veterans who were ill, providers had detailed knowledge of past medical history, comorbidities, and medications that enabled them to deliver more effective care. When COVID-19 vaccines became available, VA providers and staff could identify Veterans in specific priority groups eligible for vaccination and call them to discuss this option. This personal relationship with VA providers may have been particularly influential in helping Veterans of color receive sound advice about COVID-19 and overcome vaccine hesitancy. In addition, VA greatly expanded telehealth services and the delivery of medications to Veterans’ homes over the course of the pandemic. This has helped Veterans maintain access to healthcare without exposure to COVID-19 in healthcare settings. VA has experienced no disparities in utilization of telehealth services by race or ethnicity. VA participation in clinical trials of new therapies also enhanced the expertise of providers and treatment options available to Veterans with COVID-19 cared for at VA. VA Challenges. VA did face limitations in efforts to identify and eliminate disparities in COVID-19 care among Veterans. VA data, while accurate for identifying Black, Hispanic, and White Veterans, are less accurate for smaller groups such as American Indians, Pacific Islanders, and Veterans of more than one race. VA also lacks data on care delivered to Veterans outside of VA facilities unless a bill is submitted to VA. This is true even of care delivered by VA staff as they provided 4th Mission support outside VA facilities in State Veterans Homes, Indian Health, and other facilities. Hence, analyses of disparities are restricted to Veterans receiving care at VA. VA outreach to Veterans of color about COVID-19 also came late. COVID-19 messaging was often not tailored for specific populations or coordinated with Veterans Service Organizations and other community groups. Earlier, focused outreach to Veterans of color may have helped reduce the impact of COVID-19 in minority communities. As COVID-19 vaccination at VA continues and reaches lower risk priority groups, vaccine hesitancy and electronic sign-up for vaccination may pose a greater barrier for Veterans of color. VA will need to continue outreach efforts to ensure that all Veterans receive the evidence they need from trusted sources to make informed decisions for themselves and their families. Despite these challenges, the strong collaboration and partnership of VA program officers and researchers and the unwavering dedication of VA staff to serve all Veterans allowed VA to be proactive in identifying and addressing disparities. While always committed to equity, VA accelerated the development of tools and communities to monitor disparities and reach out to Veterans at high risk for COVID-19 infection and death. Ongoing vigilance is critical in the face of this rapidly mutating pandemic that has disrupted nearly every aspect of our modern-day existence, but safer days are coming as vaccination escalates. VA is a leader in healthcare advancements. We should redirect the knowledge we gained and infrastructure we built to mitigate disparities in COVID-19 among Veterans to other health outcomes where disparities are seen. References

|

|