|

|

Research HighlightAn Evaluation of the Telemental Health Hub ExpansionKey Points

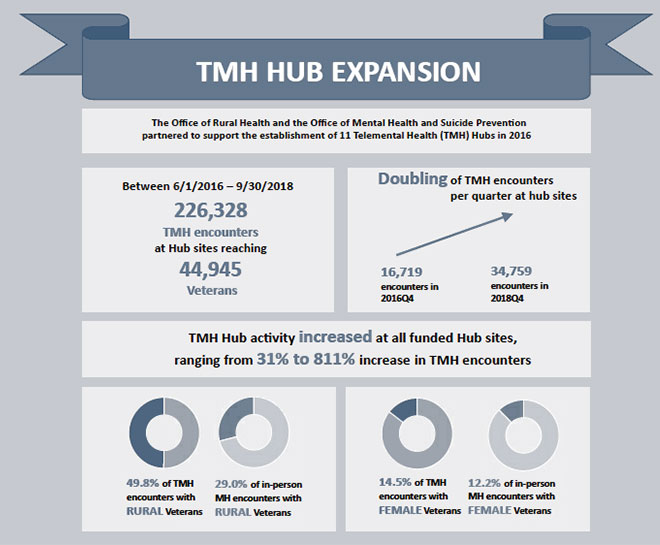

Telemental Health (TMH) is well suited to serve the needs of the 2.9 million rural Veterans currently enrolled in VA care. Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated the equivalence in outcomes of care for TMH versus in-person VA mental healthcare.1,2 In fact, VA began using interactive video to expand access to mental health care for Veterans in 1968, when three VA hospitals in Nebraska partnered with the University of Nebraska to develop VA’s first telemental health program. 3 VA’s TMH program has grown significantly in recent years, with over 3.34 million TMH encounters occurring between Fiscal Years 2002 and 2018. In an effort to increase access to mental health care for rural Veterans, the Office of Rural Health partnered with the Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention to support the establishment of 11 TMH hubs in Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs) 1, 2, 4, 7, 10, 17, 19, 20, 21, 22, and 23. Launched in 2016, these hubs fill critical gaps in mental health staffing coverage. In this article, we report on the first formal national evaluation of the impact of the TMH hubs. Using the RE-AIM (reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, maintenance) framework, our evaluation team sought to measure the impact of the 2016 TMH expansion funding on TMH activity. We further sought to contextualize this expansion activity by examining all TMH care, in-person mental health care, and primary care between 2016 and 2018. We measured reach by quantifying the number of encounters and unique Veterans served by each of the TMH hubs. We contrasted demographic traits of these Veterans with all Veterans receiving mental health care and all Veterans in active primary care. In ongoing work, we are quantifying the adoption of TMH by describing the number and types of consults placed for TMH hub services. We are also identifying the effectiveness of TMH hubs by examining the impact of TMH hub exposure on 1) mental health diagnostic rates, 2) the quality of mental health care (as measured by VA performance metrics), and 3) the incidence of adverse events. To conduct the evaluation, we identified 1) all TMH encounters, 2) all in-person mental health encounters, and 3) all primary care encounters between June 2016 and October 2018. We identified TMH activity using the Central Data Warehouse (CDW) outpatient table based on any mental health primary stop code (500 series) and a TMH related secondary stop code (136, 137, 179, 644, 645, 648, 679, 692, 693, 690). For each encounter, up to two stop codes may be recorded to document workload at the ‘hub’ site and the ‘spoke’ site. This data was de-duplicated accordingly, with a unique encounter defined as unique by patient, date, site, primary stop code, secondary stop code, and clinic location name. TMH encounters were designated as ‘expansion hub TMH’ encounters if the hub site coded encounter occurred at a TMH hub expansion site. We also identified all in-person mental health care encounters and all primary care encounters during the same period and merged Veteran demographics from CDW with these encounter files. Our analysis found that TMH hub expansion funding correlated with an increasing volume of TMH encounters across all VISNs targeted for expansion. From June 1, 2016, to September 30, 2018, hub sites experienced 226,328 TMH encounters reaching 44,945 unique Veterans. Furthermore, TMH encounters per fiscal year quarter at hub sites doubled from 16,719 encounters in 2016 Q4 to 34,759 encounters in 2018 Q4. As expansion funding began, there was substantial heterogeneity in baseline TMH hub activity across VISNs; the largest VISN had 4,988 unique TMH encounters during 2016 Q4, while the smallest had only 110 encounters However, TMH activity increased at all of the VISNs between 2016 Q4 and 2018 Q4 (ranging from a 31 percent increase to an 811 percent increase in encounters per VISN). Differences in TMH hub activity by VISN at baseline and during follow-up varied due to differences in the proposed scope, size, funding, and purpose of each hub. The TMH hub expansion program sought to increase access to mental health care for Veterans in underserved communities, especially Veterans in rural areas. Multiple findings from our evaluation indicate the program succeeded in this goal. TMH hub expansion encounters were more likely to involve Veterans at sites different than the hub site; 55 percent of TMH hub expansion encounters were to either a non-affiliated community based outpatient clinic (CBOC) spoke site or a Veteran home, compared to only 29 percent of non-hub expansion TMH activity. The TMH hub sites increased access to care for both rural Veterans and women Veterans. We found 46.5 percent of Veterans with a TMH hub encounter were rural (compared to 29.1 percent of Veterans with an in-person MH encounter) and 14.5 percent of Veterans with a TMH hub expansion encounter were female (compared to 12.2 percent of Veterans with an in-person MH encounter). Our evaluation found evidence that the TMH hub expansion funding correlated with a substantial increase in TMH encounters, especially at CBOCs not affiliated with the hub site VAMC. TMH hub expansion also increased access to mental health care for rural Veterans and to a lesser extent for women Veterans. Future work will examine the impact on detection of psychiatric disorders and quality of mental health care. The VA MISSION “Act” of 2018 requires VA to expand access to care in the community. However, it is unknown to what extent mental health care delivered in the community is comparable to VA delivered mental health care in terms of timeliness, Veteran satisfaction, and quality. As VA continues to expand community care options to increase access to care for Veterans, future work should monitor VA versus community care across these domains. Secondary data analysis of current VA data cannot answer this question, so ongoing primary data collection will be required.

References

|

|