|

|

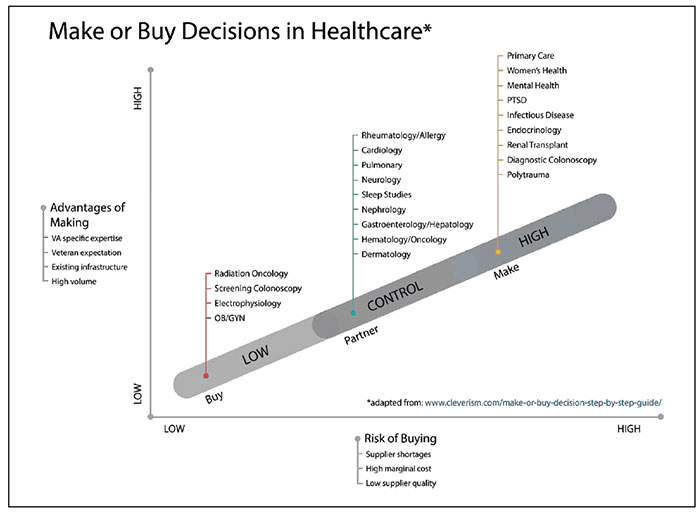

CommentarySpecialty Medical Care and the MISSION Act: A Make or Buy DecisionIn our daily lives, we are constantly presented with “make or buy” decisions. Many are easy and require little thought, like buying a shirt instead of designing and sewing it ourselves. Others, like lawn care, may involve a threshold in which we are willing to do the work ourselves, until it exceeds our skills or capacity. As with all such decisions, we make a strategic choice between producing an item or service internally, or buying it externally from another source. Healthcare systems are faced with the same dilemma. Key factors in the decision include balancing the advantages of making or providing the service (e.g., lower cost, higher quality, patient-specific needs) with buying or outsourcing advantages (e.g., low volume, unique technical needs, patient convenience). Historically VHA has navigated this balance and made reasonable trade-offs. Expansion of primary care and mental health at every medical center and community-based outpatient clinic was an investment in making a service available everywhere. Regionalization of organ transplantation, cardiac procedures, and polytrauma centers were thoughtful decisions that supported specialized expertise to provide the necessary service and maintain high quality with a trade-off of requiring some Veterans to travel greater distances. Community care for obstetrics and radiation oncology were thoughtful buy decisions. As a former Chief of Medicine, make or buy decisions occurred daily with recruitment and retention of physicians, negotiating clinic space, and following the ever-changing rules for community care. PartneringAn important middle-ground of partnering exists in make or buy decisions, especially when it involves a large organization like VHA with regional variations in supply and demand. VHA has a long history of partnering with academic medical centers in training healthcare professionals, and in providing Veterans with access to world-class expertise, especially in highly specialized medical care that would not be possible without the partnership. Close partnerships with the Department of Defense, Indian Health Service, and local providers and healthcare systems have proven beneficial for Veterans’ access to care.

Opportunity to Support Make or Buy DecisionsThe Veterans’ CHOICE and MISSION Acts have created a new opportunity for VHA to evaluate past make or buy decisions and propose new models to advance access to care from both the subjective patient perspective and objective costs and wait times. 1 This opportunity also requires careful attention to the quality of care provided so it can be measured, maintained, and even improved. The MISSION Act has the potential to facilitate both make and buy decisions for VHA; provisions to increase funding will help accomplish both. On the “make” side, the Act enhances capacity through provisions to recruit and retain healthcare professionals. Strengthening and building new academic affiliations can improve recruitment through debt reduction and scholarships, professional growth opportunities, and optimizing visa waiver programs. Another provision removes barriers to telemedicine by shifting excess capacity in one region to another. It also supports the sharing of highly specialized expertise to a larger proportion of Veterans across VA healthcare systems. VHA has already accomplished improved access to telemedicine through tele-ICU networks, tele-stroke, tele-dermatology, and recently tele-hospitalists. Electronic consults also provide an innovative solution to shift demand to locations where supply is higher and obviate the need to buy the service. Some medical specialties are more amenable to e-consults, particularly those that are mostly cognitive. Infectious disease, hematology, and endocrinology services currently provide over 10 percent of their consults in VA through e-consults, whereas specialties that depend more on the physical exam during an in-person visit (e.g., dermatology, neurology, cardiology) employ e-consults for less than 5 percent of visits. On the “buy” side, a key provision authorizes local provider agreements. Those who provide care in a VA within a community of inter-related healthcare systems know best what expertise and capacity is available and where. Third party administrators, through no fault of their own, are challenged to foster these relationships in a community and coordinate care. Building these relationships is mutually beneficial for community and VA providers, but most importantly, these relationships benefit our patients. Provider and patient education, advanced scheduling systems, and improved health information exchange will also facilitate the buy side of the decision. Underserved VA Medical FacilitiesThe provision to establish criteria to designate VHA facilities as underserved is analogous to medically underserved designations made by the Department of Health and Human Services. Criteria will need to include ratios of providers to Veterans, specialties provided, local community resources, and wait time metrics. Care will be needed to ensure resources are not used simply to reward poor past performance, but instead create cost-effective solutions to complex access issues, especially in rural areas. PitfallsAlthough not all pitfalls can be predicted, there are several considerations that can impact make or buy decisions. For example, highly technical, low volume services (e.g., obstetrics, radiation oncology) will likely remain in the buy category; provider agreements and local collaboration can ensure excellent care. Each specialty will need to determine what services they can provide based upon the expertise and capacity available and what should be bought. One-time procedures may be more easily outsourced (e.g., screening colonoscopy), but not ones that require ongoing relationships with a physician (e.g., colon cancer surveillance for inflammatory bowel disease). A few provisions, such as mobile deployment teams to help facilities struggling with access, will be piloted and evaluated to ensure they are practical and effective. Coverage of “walk-in” visits to eligible non-VA clinics or Federally Qualified Health Clinics will offer improved access, especially for low acuity conditions, but two-way sharing of medical records will be critical to ensure continuity of care. Quality of care will be an ongoing challenge. For many conditions and specialties, it is difficult enough to measure quality within a healthcare system, but even harder to assess care provided by another system. Robust sharing through electronic health record portals will be required not only to prevent information loss and adverse events, but also to include quality metrics as part of the ongoing relationship. Ultimately, specialty medicine services will need to address make or buy decisions locally, but with guidance from national expertise, partnered evaluations, and investigator-initiated research. Leveraging the talent and commitment of VHA clinical leaders, administrators, and researchers will not only improve access to care for Veterans, but move VHA along the path to becoming a Learning Healthcare System. Reference

|

|

Next ❯