|

|

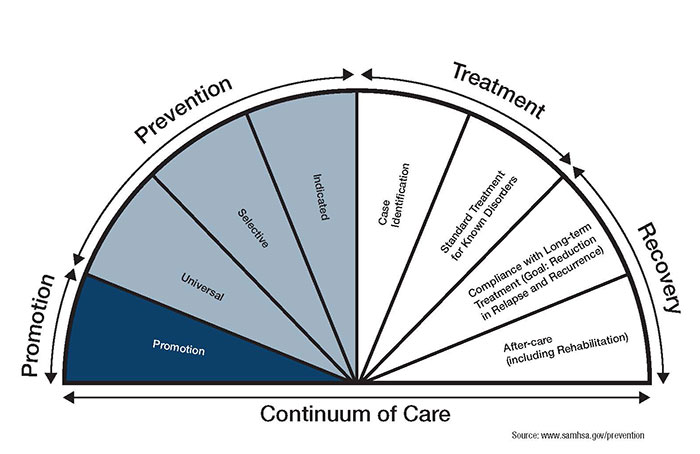

Response to CommentaryA Public Health Framework Suggests Five Challenges for Suicide PreventionVHA has committed substantial resources to understanding the prevalence and impacts of suicide among Veterans, its risk factors, and approaches to reducing suicide and suicide behaviors. Gaps remain, however, in many aspects of suicide research, and innovative approaches are needed. Eric Caine, MD, an eminent suicide researcher, recently argued for "broadly based public health approaches that reach beyond the current methods of finding individuals deemed to be at imminent risk to die," and presented a series of challenges for suicide prevention that have yet to be addressed.1 Twenty-five years ago, the Institute of Medicine proposed a framework for organizing population-based prevention strategies: 1) universal strategies are designed to reach an entire population to prevent or delay onset of the problem; 2) selective prevention strategies identify and target subsets of the population who have been identified to be at risk; and 3) indicated strategies are designed to prevent negative consequences among individuals at confirmed risk.2 Here we present five VHA and health services-specific challenges, outlined below, that cut across these prevention domains. Key Points Applying a public health framework can identify clinical and research needs for suicide prevention.

Challenge 1: Match Veterans' needs to the appropriate type and intensity of services.VHA is currently funding a number of research and operations projects focused on optimizing screening, risk assessment, and risk stratification. Projects in this category generally fall into the selective prevention domain. One such project, REACH VET (Recovery Engagement and Coordination for Health-Veterans Enhanced Treatment), uses a predictive analytic approach with administrative data to identify Veterans at high risk for suicide. While REACH VET and other new risk stratification tools are important developments, there is currently little scientific evidence to guide tailoring of treatment approaches to levels of identified risk. The field has not yet rigorously examined how to best prepare clinicians and care teams to use such data in care. There are also gaps in our ability to estimate and respond to suicide risk as it changes over time—suicidal intent and action are frequently transient. Additional research incorporating temporality into risk stratification, clinical decision-making, and programming is needed. Challenge 2: Prepare, activate, and support Veterans to use available healthcare services.Strategies to address this challenge mostly fall within the domains of universal and selective prevention. For example, Mark Ilgen, PhD, is conducting a clinical trial that prepares Veterans to call the VA Crisis Line. In this study, at-risk Veterans literally practice calling the Crisis Line before they need it. Marianne Goodman, MD, is conducting several projects that involve family members in safety planning, a key goal being for them to support Veterans in accessing VHA care when it is needed. In general, however, VHA researchers are currently conducting few projects addressing this challenge. Challenge 3: Expand suicide prevention efforts upstream and to Veterans who do not receive VHA care.This challenge also addresses universal and selective prevention strategies. The Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention is leading substantial outreach efforts targeting both the VHA internal and larger non-VHA communities. Elizabeth Karras, PhD, is conducting projects evaluating VHA's suicide prevention communication strategies related to firearms messaging and the Make the Connection online resource, respectively. Overall, however, little research is being conducted to address this challenge. Looking forward, research opportunities here include exploring impacts of VHA's Whole Health and Primary Care Mental Health Integration Initiatives, wider spread implementation of lethal means safety counseling, and enhanced use of social media on suicide awareness, education, and treatment-seeking. Challenge 4: Coordinate strategies and services to optimize positive outcomes and reduce negative consequences.VA and the Department of Defense (DoD) are conducting several projects that examine transitions in care. One project in the indicated domain, Home-Based Mental Health Evaluation trial, led by Bridget Matarazzo, PsyD, is testing an intervention to help Veterans engage in outpatient care following inpatient psychiatric hospitalization. Key knowledge gaps related to this challenge include understanding how to best coordinate care transitions from DoD to VA, how to successfully coordinate (and leverage) care between community and VA care settings, and how to leverage information technology and telehealth solutions to improve suicide prevention.

Challenge 5: Scale, implement, sustain, and ensure fidelity to existing evidence-based and promising interventions.VA and other agencies have recently funded a number of clinical trials and pilot projects that fall into the indicated prevention domain. Evidence is beginning to accrue that some brief psychotherapy interventions reduce suicide behaviors.3 To date, however, researchers have not conducted large-scale pragmatic or implementation trials in VHA to test methods for expanding access to these promising treatments. It is also unclear what the best approaches are for ensuring fidelity to promising interventions as they are rolled out. In their FORUM commentary, Lisa Brenner, PhD, and colleagues highlight the need for a public health approach to suicide prevention. The challenges described above call for a range of approaches that cut across all levels of risk. Although important work is being done in each of the prevention domains, the universal domain is relatively underrepresented. If VHA is to adopt a public health approach—particularly one that reaches Veterans outside of VHA—we must continue to prioritize efforts to design and fund projects that focus upstream. This includes projects that: 1) improve delivery of, and Veteran participation in, high quality treatments for conditions that increase risk for suicide; and 2) develop and test approaches that educate, activate, and support Veterans with known and unknown levels of suicide risk, as well as their families and communities, in accessing care when it is needed. These ideas were developed in collaboration with Peter Mills, PhD, and presented at a VHA/DoD-sponsored meeting in December 2017, which reviewed the suicide prevention research portfolio across VHA, DoD, and other partners and agencies. References

|

|